‘Nothing Ever Replaces Expertise’

Published November 25, 2020

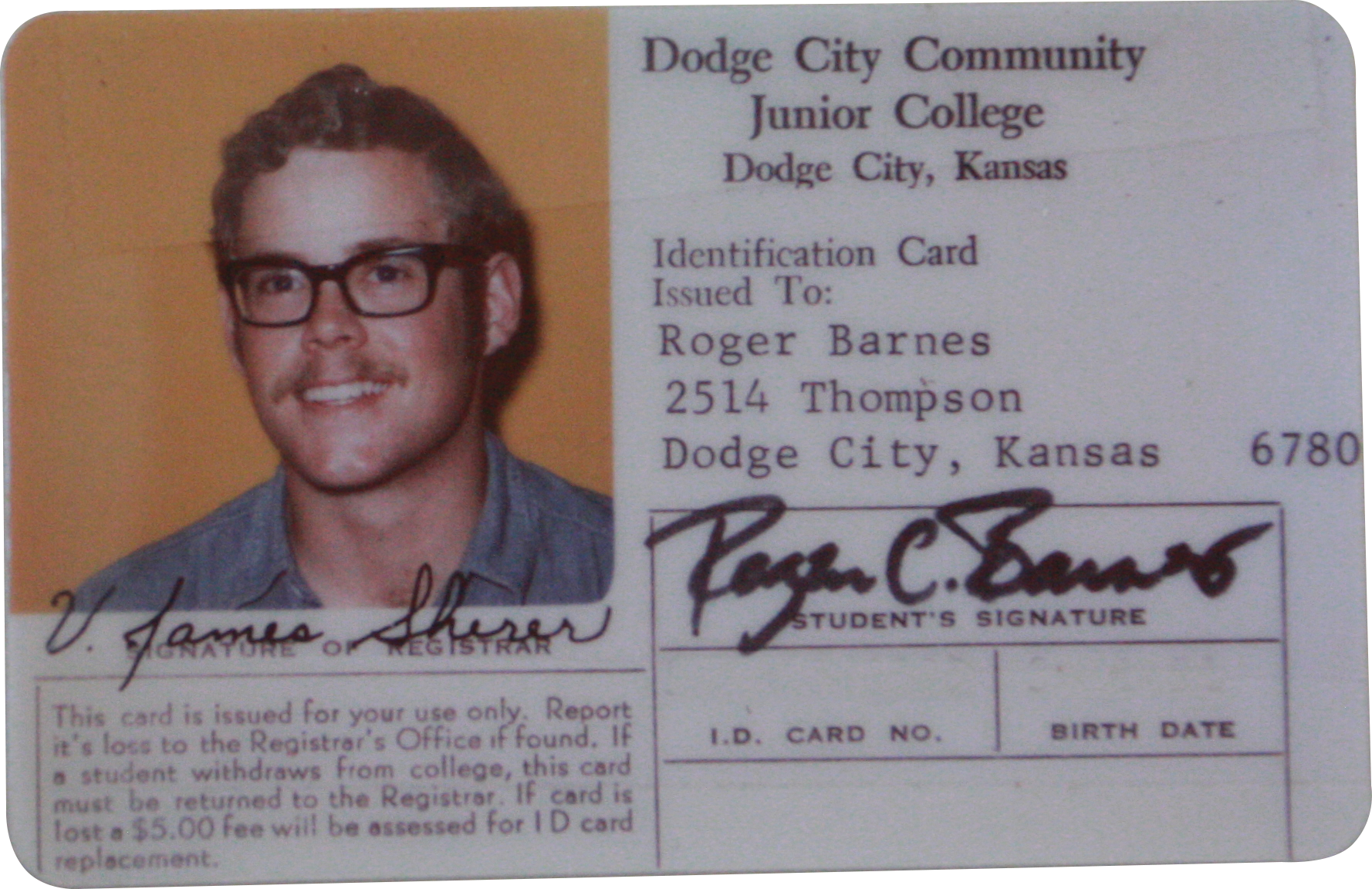

Dr. Roger Barnes, son of DC3’s longest-serving president, reflects on his dad’s legacy

For Dr. Roger Barnes, Dodge City Community College (DC3) is far more than a two-year school he attended before transferring to the University of Kansas. It’s also like home, because he actually grew up with the college.

PART TWO OF A THREE-PART SERIES

The new campus

“They bought the land from Jim Mooney, who was a farmer,” Barnes said. “His son was in my class.”

At the time of the land purchase, the U.S. Highway 50 bypass was the northern boundary of Dodge City, and the Mooney farm was at the corner of town, he said.

“There was nothing on the other side except fields,” he said. “So, putting the college out there turned out to be a really good move.”

After purchasing the Mooney property on Feb. 6, 1967, the college hosted a groundbreaking ceremony at the site on May 26, 1968, and the campus construction officially began that June.

The new campus was designed by a Houston-based architectural firm called Caudill Rowlett Scott. And one of the firm’s key representatives was as guy named Truitt Garrison.

“He [Garrison] made numerous visits to Dodge City, back and forth,” Barnes said. “He would come over to the house, and he and my dad would look at these blueprints and these plans. The two of them together would say, ‘Well maybe, we ought to move this over here and move this over to here.’ It was fun to watch the college grow up, brick by brick, on what had previously been a cow pasture,” he said.

“It wasn’t like you were just adding a new building. You were adding all new buildings, all new facilities, everything boom at once!” he said. “I think it is one of the prettiest community college campuses in the state, if not the entire region. I think it was a huge accomplishment.”

For its design of the DC3 campus, Caudill Rowlett Scott would later receive an Honor Award from the Texas Society of Architects in 1971.

Although the new campus would open for classes after the 1970 spring break, its official dedication would not be until Oct. 25, 1970.

Moving from Second Avenue to the new campus was a “day and night” difference, Barnes said. The Conquistadors had gone from a tired old building, with its dilapidated houses across the street, to a brand new 143-acre campus with “these marvelously designed” buildings.

“When we arrived at the new campus, it was new,” he said. “Everything was new. Offices, facilities, everything. It was beautiful. Maybe today they are not so spectacular, but 50 years ago they were cool.”

Everyone was excited about moving to the new campus, Barnes said. And everyone also pitched in—faculty, staff and students—to make it happen.

“We used our own cars,” he said. “It was a big collective effort. Faculty, staff, students—we moved the whole college, kit and caboodle, pretty much all at one time. And nothing really remained down on Second Avenue.”

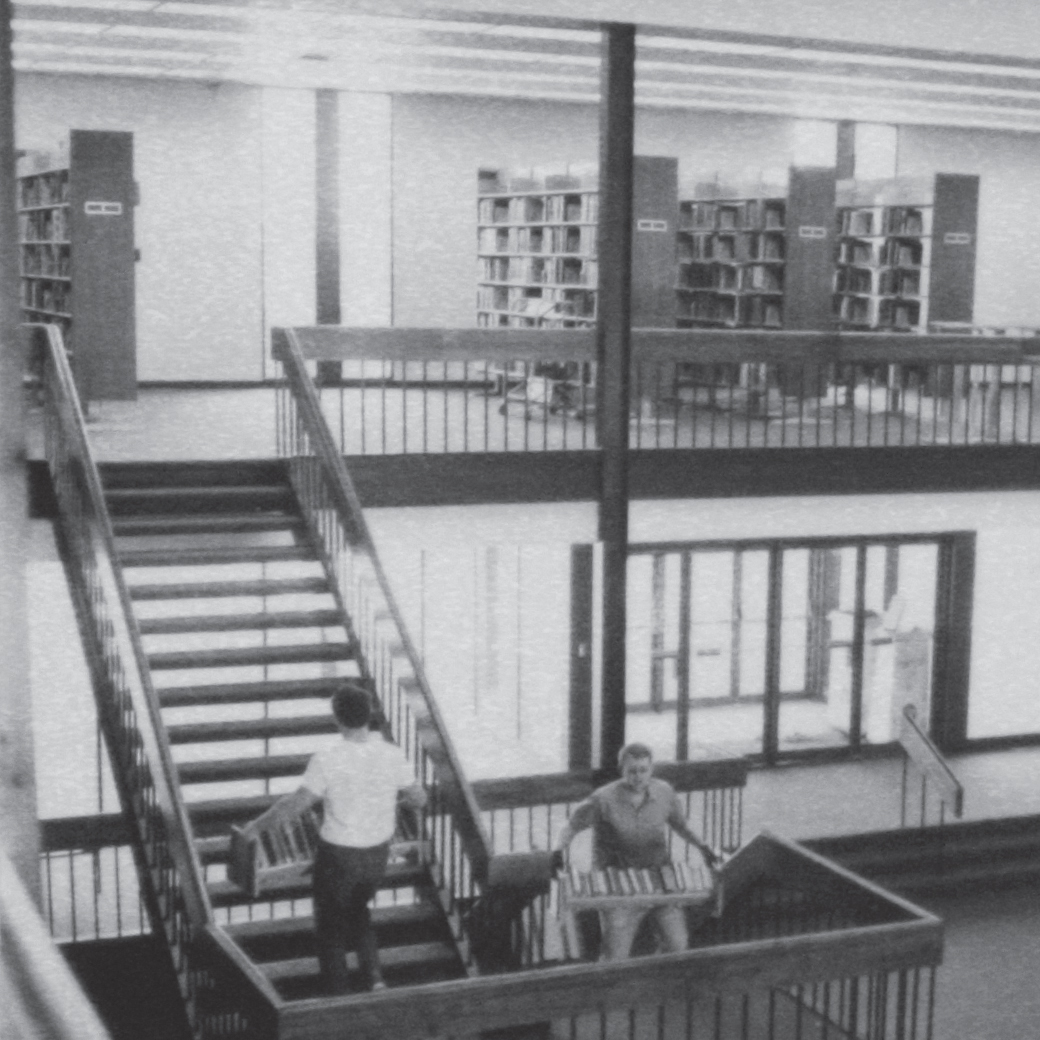

Because Barnes was a work-study student in the DC3 library, he was involved in a “very interesting system” devised by the head librarian, Audria Shelden, to move the books to the new campus.

“They had trays made… We could just take the books off the shelves, put them on these carrying trays, and move them that way,” he said. “So, we didn’t take the books out of order, and it made re-shelving [relatively] easy.”

Once everything was in place, Barnes said the new campus gave everyone “a whole lot of spirit, and a lot of verve, and a lot of energy.” This was especially true for the drama and music students, he said.

“You take a look at the old auditorium, which was a tiny little inky-dinky thing on the first floor of the building on Second Avenue. And then you look at the new theatre, and it was the difference between night and day,” he said. “The kids had this beautiful theatre to work in now, and not some cramped little stage. And the kids who were in band, now had a band room… with rehearsal rooms.”

Looking back on the differences between the old and new campuses, Barnes said he thought the new campus also helped to compensate some of the longtime faculty for their years of service on Second Avenue.

“Keeping those good teachers—people like J. Paul Shelden, Bryce Gleckler, Vernon Zollars, Winifred Russell, Francis Revitte, George Harshberger and others—and then giving them this brand new campus to work with was a real reward,” he said.

“They deserved it because they were good people. They were knowledgeable folks. While they didn’t have PhD degrees, that didn’t diminish their teaching capacity one iota,” Barnes said.

“My dad once told me, ‘Remember Rog, nothing ever replaces expertise.’ And I look back at the faculty that he had back in those days, and he had a darn good faculty,” he said. “He had some people who had quite a measure of expertise.”

Roger attends DC3

After graduating from Dodge City High School in spring 1969, Barnes decided to continue his education at DC3 that fall. And after graduating from DC3 in 1971, he would later transfer to the University of Kansas. However, while at DC3, Barnes also would meet the love of his life, Karin Kessinger, who would later become his wife.

“When I started in 1969, in the fall, we were down on Second Avenue in the old building,” he said. “And so we moved in the spring of 1970 from the old building out to the new campus, and Karin arrived in the summer of 1970. She started working in the library for Mrs. Shelden. And the library is where we met in early September 1970, and the rest of that is history, as they say.”

Growing up with the college as he did, Barnes said he knew most of the faculty as family friends, well before he started classes as a student. Through the years, many of them had come over to his parents’ house for bridge or other activities, and some had played golf with his dad.

“I knew the faculty, and they knew me as a little kid, but I didn’t get any preferential treatment,” he said. “If I did, I wasn’t aware of it, and I also didn’t catch any grief.”

Of course, he said the president of any school is going to make decisions that people are not going to like, and sometimes those decisions will affect how people interact with the president’s family. But as a whole, having his dad as president while he was on campus “was not a bad thing at all.”

Barnes remembers walking by his dad’s office in the Administration building, which at the time, was also where the Board of Trustees met. This office, which is occupied today by the vice president of academic affairs, was located on the south end of that building.

“I would walk by on the outside, knock on the window and wave at him, and then just keep walking on,” he said. “I pretty much tried not to bug him when I was there. I knew he had things he had to do.”

So, although his college experience at DC3 was mostly like that of other students, there were other times when it was a little uncomfortable being the president’s son, he said.

“It was a little bit mixed when I started in 1969 because the Board had made… the decision to drop football, and I mean to tell you, it was a mess,” he said. “All of those kids who wanted to play football, and their parents, were really unhappy. It was very unpleasant to be my dad’s son [at that point], because he came under a lot of fire.”

Although that decision had been made by the Board of Trustees as a cost-saving device, his dad became the face of the matter to the students and to the public, he said.

“The Board is this kind of amorphous group of people who are very remote, in so far as most faculty and students know,” he said. “So, the one guy you could focus your discontent on was my dad. But, the Board changed that decision, and they were back to football the following year. I think everybody was very happy with that decision.”

By Lance Ziesch

DC3 Media Specialist

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in the Fall 2020 issue of the Conquistador. The Conquistador, which is the official magazine of Dodge City Community College, is published once per semester. Copies of each issue are available on campus or online at dc3.edu/media2/magazine/.