College Vice President Keeps Creative Spirit Alive

Published September 28, 2018

“It’s having a reflective stance on our own lives, which I would hope we all do.”– Dr. Jane Holwerda

Dr. Jane Holwerda is the vice president of Academic Affairs at Dodge City Community College, but she is a creative and reflective English major at heart.

Holwerda has long kept that spirit alive, publishing dozens of poems, memoirs and short stories over time. Earlier this month Holwerda was awarded the Paul Somers Creative Prose Prize by the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature for her short story “Vanishing Point.”

Inspiration for the story came after listening to Viet Nam War veteran and novelist Tim O’Brien speak at an SSML conference. A call went out for papers and presentations about O’Brien’s work or pieces regarding similar themes.

Not having a veteran’s perspective, Holwerda considered how she could speak to O’Brien’s canon of work.

“I’m not a veteran, but I thought I could imagine how it would be to be the mother of a veteran,” Holwerda said.

“Vanishing Point” tells of the grief and anguished soul-searching of a widowed mother at the wake of her son, who had returned broken from war 30 years prior and gradually crumbles into a shattered, introverted existence. The mother comes to realize that she had lived decades suspended in the perception of her son as the vibrant, genial young man he had been before the war.

Holwerda has discovered a common theme running through much of her work. She says it’s more of a “preoccupation” with the motif of people living in the past despite ample evidence of a very real present. She says many of us exist like a pre-historic mosquito locked inside a chunk of amber – capturing a moment in time, unchanging and unaware of changes happening all around.

“Some of us of a certain age lose contact with the passing of time,” she said. “We get captured in an earlier version of ourselves and don’t realize that we haven’t grown or changed. In ‘Vanishing Point’ we realize that the main character had not seen how her son had evolved because she herself had not evolved. I think we often live in that notion of our earlier selves.”

She says the theme is a natural consequence of writing memoir and effecting a reflective posture toward life. “When we write about events in our lives we are looking back and considering ourselves in the present,” Holwerda said. “It’s having a reflective stance on our own lives, which I would hope we all do. There’s the old axiom that says ‘The unexamined life is not worth living.’”

In the past several years, many of Holwerda’s short stories have examined themes related to living in small communities. Her stories often explore the challenges of fostering some sophistication and culture in places that may not value those principles as highly.

“How does a person cultivate and nurture those elements of the self that maybe are not widely celebrated in a small, rural community?” Holwerda remarked.

She said her work writing and recording BookBytes for High Plains Public Radio has helped her discover and see more concretely particular aspects of rural society. Organizers of HPPR’s Radio Readers Book Club try to select books that speak to concerns of people living on the High Plains.

Holwerda was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2001 for her poem “Worst Things.” Her story “Faith Healer” was a finalist for the Short Fiction Prize from Jabberwock Review in 2017. She won the 2016 Spiritual Nonfiction Prize from Ruminate Magazine for “Quo Vadis, Slayer” – which was also a Pushcart nominee.

Her work is featured in the internationally published anthology “Guilty Pleasures: Indulgences, Addictions, and Obsessions,” a collection of 21 humorous essays by an octet of Midwestern women who joined together several years ago to form a group informally known as the Doves. “Guilty Pleasures” features stories like How to Prepare for and Secure the Perfect Daytime Nap, Milking Parents for Cash, as well as satirical looks at their on-again, off-again obsession with food, eBay, toenail polishing procedure, and gossiping.

Holwerda’s academic and professional career has come about as a result of an almost purposeful lack of strategy, other than strategically identifying paths in life that she finds enriching and edifying, and allowing those paths to lead her where they may.

“I’m not one of those persons who have had a mapped-out life,” Holwerda said. “I kind of wander along life’s road and make a turn when it seem like there might be something interesting in that direction.”

She majored in literature mostly because she enjoyed the professors and appreciated the reading material. Even upon graduation she was unsure of what she wanted to do next. A professor encouraged her to grad school and she casually agreed.

She said she approached college and much of life with the same attitude. When presented with an opportunity she considers … “That might be interesting. What can I learn doing that … how can I help others?”

Holwerda taught English for several years but continued to write. “I always wanted to be a writer with a capital W,” she said. “Literature diverted my attention for a while but it was good training. Teaching was a great companion to the writing life as well.”

Her work in grad school reflected the unconventional, virtually extemporaneous path Holwerda chooses to walk. She took some graduate classes in areas beyond traditional literature and English, eventually settling on American Studies – a multi-disciplinary program that casts a wide net regarding course choices for students.

The combination of disciplines and broad liberal arts course offerings appealed to Holwerda. “As long as thematically the classes were about American culture, I got to take them. I took American literature, political theory, some theology, some communication theory, some sociology.”

Once she earned her doctorate in American Studies, Holwerda eventually made her way into teaching. She came to DC3 in 2003 as an English professor, teaching classes and serving as the Humanities department chair until DC3 President Harold Nolte tabbed her for administration.

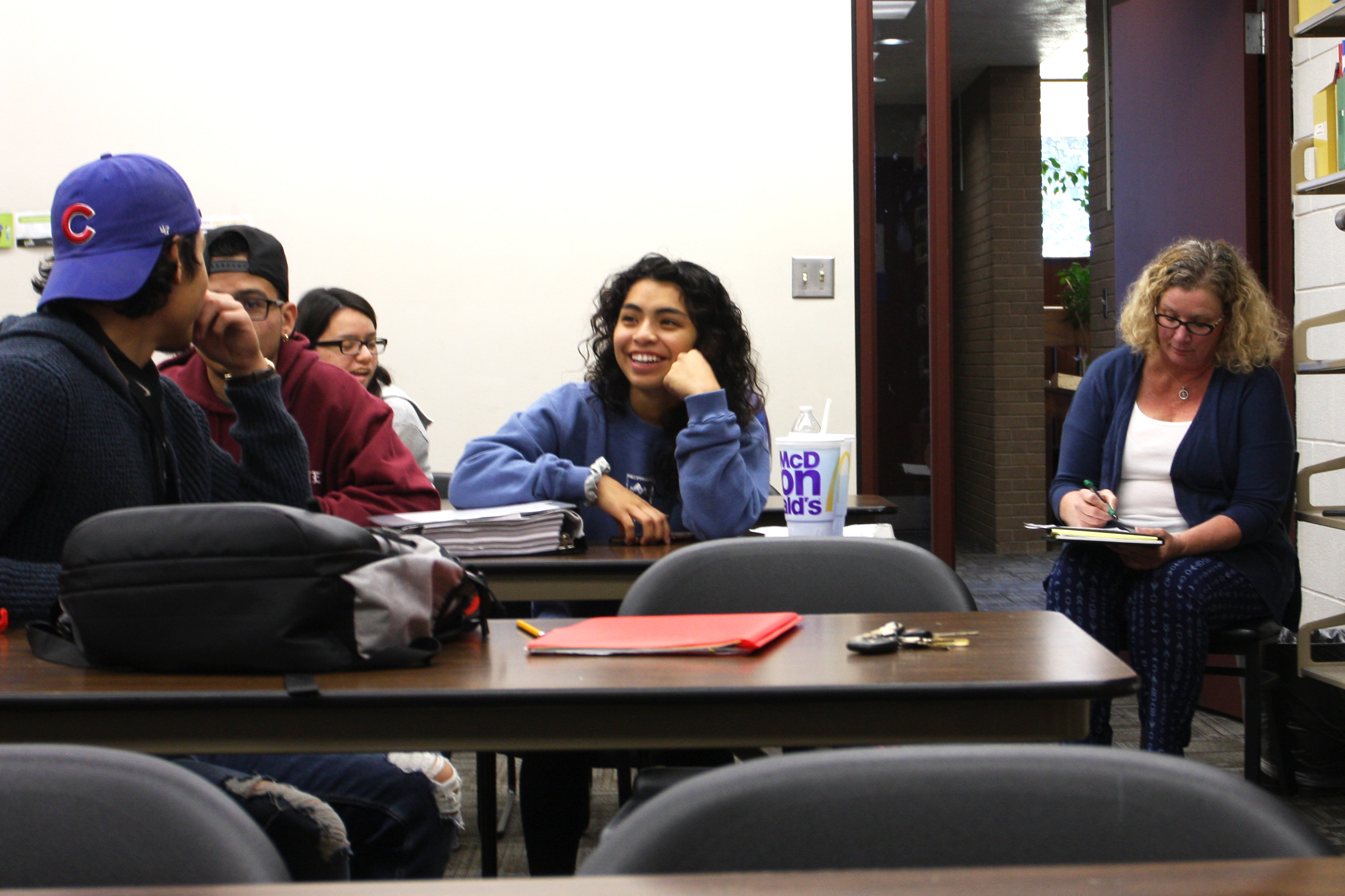

Holwerda says she does miss teaching but she enjoys her current role – guiding and mentoring faculty.

“Teaching is the most important part of what we do, particularly at a community college” she said. “I miss it but I am so proud of the faculty that we have. I try to convince myself that I still have a teaching role, it’s just a different type of teaching. The teaching I do know is to help our faculty, especially those early in their careers, to develop their skills and their classroom style – though they probably don’t need me to help them very much with that. They’re just amazing.”

By Scott Edger