The Dollars and ‘Sense’ of College Rodeo

Published December 14, 2021

Unlike other student-athletes at Dodge City Community College (DC3), members of the rodeo team are financially responsible for their own gear, animals and competition fees.

Unlike other student-athletes at Dodge City Community College (DC3), members of the rodeo team are financially responsible for their own gear, animals and competition fees.

In fact, some rodeo athletes may have invested more than $50,000 in rodeo equipment and assets before they even step foot on campus. However, no matter how large the dollar figure is, students say the rodeo experience is worth every penny.

Jarrod Ford, who became the DC3 head rodeo coach on July 1, said the 2021-22 rodeo team is made up of 15 student-athletes—from Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas and Ontario, Canada—who compete in a variety of events such as breakaway roping, team roping, goat tying, barrel racing, bull riding, bareback riding and bronc riding.

Of the 15 rodeo members, 14 of them already have bought the necessary National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association (NIRA) card, which makes them eligible for college rodeo competition this academic year.

“They have to buy that in order to compete at college rodeos, and they have to send in their transcripts to show that they’re eligible,” Ford said. “They have to keep at least a 2.0 cumulative GPA throughout the year combined, and they have to take at least 12 credit hours and pass at least nine of them.”

The NIRA card, which costs $275, is just one of the expenses rodeo student-athletes have to cover in order to compete. They have to cover a lot of their rodeo traveling expenses on their own as well, he said.

“Right now we don’t have a huge team, so we buy a room for everybody that enters the rodeo,” he said. “There’s usually a men’s room and two women’s rooms. And then if they’re on the points team, they can get travel money.”

The points team, which is made up of six men and four women, is determined by Ford and the other two assistant rodeo coaches, Tyrel Moffitt and Erica Edmondson, before each rodeo.

“It will change often,” he said. “If they’re somebody that’s week in, week out, getting points for the team, they’re probably going to be on the team,” he said, referring to student-athletes who regularly bring home individual points because of their placings. “If somebody is not getting points, we may swap out each week and just try finding the right one that hits.”

However, Ford said it’s also possible for rodeo members who win every week, to not be included on the points team due to disciplinary actions. If they skip practice, are late to practice, or are getting into trouble off campus, they can lose their place on the points team, which means they also will lose the extra travel money, he said.

“It’s $75 a weekend that they get,” he said. “They can use that towards fees. They can use it towards fuel. They can use it for food or whatever they want to use it on. But then it’s on them to get to the rodeos.”

Although DC3 does own a truck and trailer, which is available for team use, most rodeo student-athletes would rather take their own rigs and share expenses with teammates, he said.

“Rodeo is weird. At college, it’s a team sport, because there is a points team. But it’s also an individual thing, because you’ve got the chance to make it to the college finals as an individual,” he said. “They take the top three from each event as individuals to the college finals, but yet, they will take the top two teams in men’s and women’s to the college finals. So there’s a chance to make it both ways.”

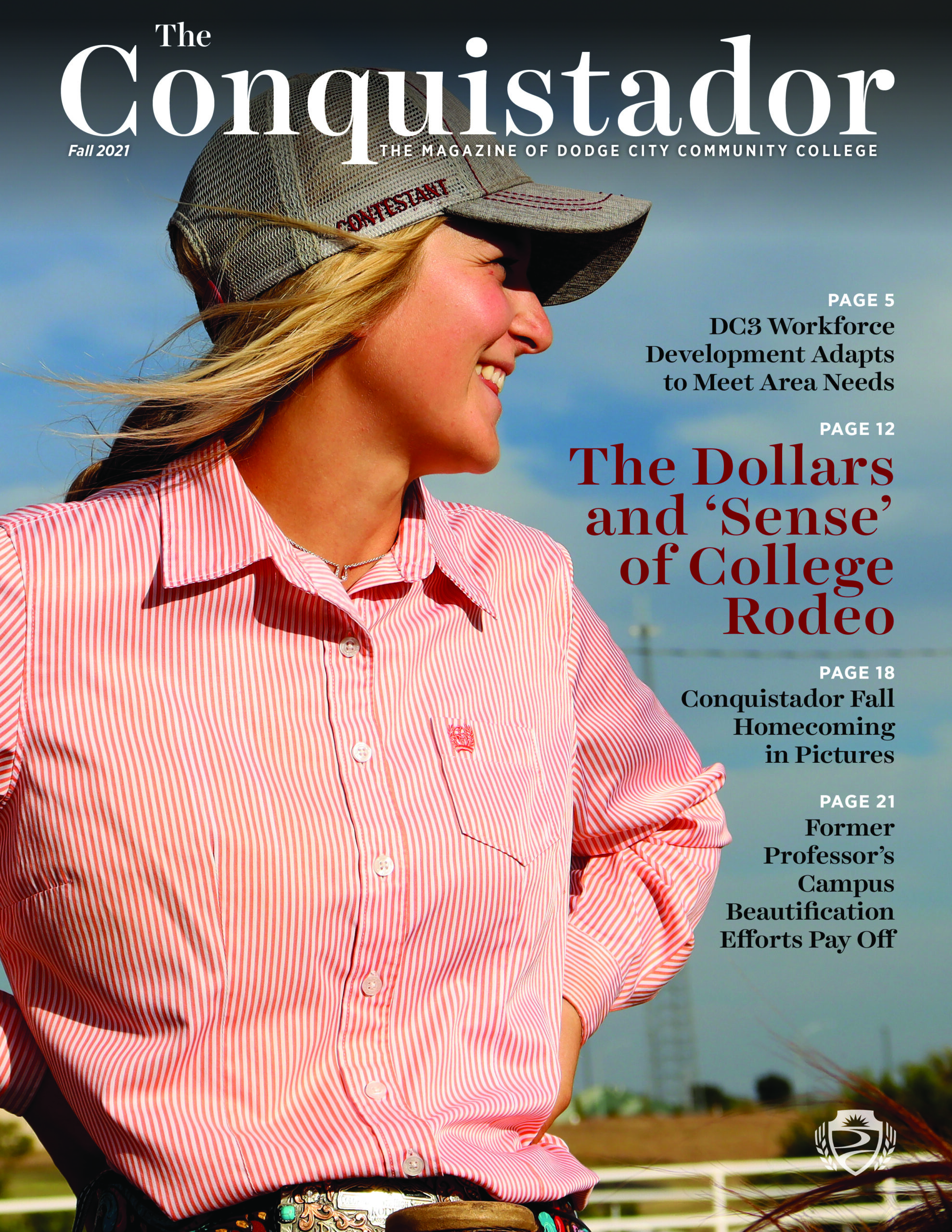

![Taylor Davis [Photo by Luke Fay]](https://dc3.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/IMG_1833-scaled.jpg)

Taylor Davis [Photo by Luke Fay]

Taylor Davis

Taylor Davis, who is a sophomore from Rifle, Colo., became involved in the sport of rodeo around the age of 6 or 7.

“My parents first started me on mules because they had mules,” Davis said. “Then, I had a horse given to me, which actually got me into the whole rodeo aspect of things.”

So, although she didn’t come from a rodeo family, she started getting involved after becoming a horse owner, by competing in National Little Britches Rodeo Association events.

Little Britches, which is one of the oldest youth-based rodeo organizations, sanctions rodeos in 33 states for children ages 5 to 18.

“After I got this horse, I started riding him, and we got some help from other people,” she said. “I started off in Little Britches. And then from there, I just kind of started into junior high and high school rodeo.”

Growing up in the Little Britches organization, Davis competed in ribbon roping, breakaway roping, goat tying, pole bending, and barrel racing. And today, she competes in goat tying, breakaway roping and barrel racing.

“I would say goat tying is definitely my favorite,” she said. “It’s like a solo event. You and your horse, instead of like team roping or something like that.”

Another component to her competition is caring for her horses, Davis said. Not only does she have to board her own horses at DC3, she also has to feed and care for them.

“Most of us do twice a day,” she said, in regards to feeding schedules. “So, we get up before school and feed them. Then at night we feed them again.”

Regarding the feed itself, Davis said she brings hay that her dad put up at home. However, because of the continuing drought conditions around the country, hay is getting expensive.

“We cut and do our own hay at home, so we just load up a flatbed and bring it out here,” she said. “So, I brought 100 bales… and I put it in my shed by my horses, so I can feed them.”

If she had to pay for those 100 bales herself, she said she would be looking at roughly somewhere between $7 and $13 a bale.

Ford said he agrees that it takes a lot of money to keep a rodeo horse going—whether it’s the vet bills, equipment, grain costs or that $13 bale hay “that lasts a day and a half.”

“You’re not only taking care of yourself, but for timed events, you’re putting into those animals that are your lifeline,” he said. “I mean, without them, you can’t do anything.”

And then there’s the cost of the horses themselves, he said.

“The horse might cost $50,000 to $75,000,” Ford said. “Depending on your horse, it could be up to $150,000. It’s a very money-demanding sport.”

Although Davis started out at DC3 with three horses, she currently only boards two at the college.

“Since I’m in three events, I have a barrel horse,” she said. “So, I ride her pretty much just for barrels. She’s younger. She’s 7, so she has a lot to learn. And then my other horse, I have him for goats and breakaway.”

Additionally, Davis said that she gives her older horse grain each morning and night, along with his regular feed.

“I have to grain my horse morning and night, you know, because he’s older,” she said. “It just helps keep the weight on him and gives him a little bit more energy.”

Davis said it’s important to have more than one horse at college, because rodeo horses get used so much day in and day out. And sometimes, they can get injured as well.

“They’re going to get tired. They’re going to get sore,” she said. “It’s good to give them a little bit of a break. And then when you’re hauling from rodeo to rodeo, if you have two horses, it kind of puts less stress on the other horse.”

Although Davis can ultimately do every one of her events on her older horse, she tends to save him for only goat tying and breakaway roping.

“If my younger horse wasn’t really working right for me, I would change to him,” she said. “But now like if my breakaway horse got hurt, I wouldn’t be able to use my younger one, just because she doesn’t really know anything yet. I kind of just started her in the breakaway, but she’s not really finished, and she doesn’t really understand that aspect yet.”

In addition to twice-a-day feedings, daily exercise with both animals, Davis also has to keep her horses’ stalls clean.

“We have to clean our pens at least once a week,” she said. “Although, they should really be cleaned every day. And then exercising your horses is important. If you don’t exercise them enough, their legs can actually stock up and start to swell, which is not good at all.”

![Taylor Davis ropes a calf during rodeo practice on Sept. 27. [Photo by Lance Ziesch]](https://dc3.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/IMG_1984-scaled.jpg)

Taylor Davis ropes a calf during rodeo practice on Sept. 27. [Photo by Lance Ziesch]

Since Davis competes in three events at every rodeo, she also has to pay entry fees for each of them before she can participate.

“For me total, it’s usually $175 for all three events,” she said. “And then if you were to make the short round or something, there’s a jackpot fee that you have to pay.”

So, for rodeo student-athletes, in addition to the costs of buying their animals, the cost of feeding their animals, and the cost of their rodeo entry fees, they also have to pay for their transportation and gear, she said.

“Ballpark costs are easily over $50,000 that you have to bring,” she said. “The tack, the truck, the trailer… it’s a lot of responsibility.”

But along with all of the responsibility, Davis said rodeo also has given her a lot of opportunities to travel and meet people. It’s also helped give her a good work ethic.

“You get to meet new people. You get to see new things,” she said. “In rodeo, a lot of people help other people out. It teaches you how to be a team player and how to help people when they need help.”

Davis said her favorite moment from her freshman year at DC3 was when she made her first ‘short go’ at a college rodeo in Weatherford, Okla. In rodeo, the short go is the championship round of an individual event competition, which is limited to the top 10 placing contestants from the previous rounds.

“I was up the first night in the performance, so I had to go through about 50 other goat tiers. I was really stressing about where I was standing,” she said, referring to her place in the rankings. “Well I made it back in that one, and it was my first one ever. So I would say that would be my favorite memory.”

In addition to the short go, there is also another term used in rodeo competition: slack or slack performance. Slack is basically the overflow for contestants who compete in calf roping, team roping, barrel racing, and steer wrestling. It helps allow for as many people as possible to compete, as only 10 contestants can be in the performance.

Whether or not rodeo athletes compete in a slack or a competition is not based on their abilities or standings, but instead is determined entirely by chance, Ford said. Although they might prefer one or the other, it’s all ultimately up to how they draw.

“When they enter, they get preferences. They put down what performance they want to try for or if they want slack or whatever,” Ford said. “Then they just draw randomly their position and what performance or slack they get,” he said.

After DC3, Davis plans to pursue a career in nursing. However, she said she still has long-term plans for rodeo.

“I want to be a flight nurse,” she said. “So that also gives me time to be able to rodeo at the same time, because I do want to end up going pro. So, between nursing, I can be a travel nurse and kind of hit rodeo to rodeo.”

Although keeping up with her studies while attending weekend rodeos is a challenge, Davis said her instructors go the extra mile to help her succeed.

“They work with you a lot,” she said, speaking about her instructors at DC3. “But it’s still challenging because every day I’m up till like midnight just trying to get my schoolwork done.”

And on rodeo weekends, things are especially hectic, she said.

“For the Oklahoma rodeos, we leave Thursday, Friday and Saturday,” she said. “But the Kansas ones are just for the weekend. So I do miss a lot of school.”

![Tyler Bauer [Photo by Lance Ziesch]](https://dc3.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/IMG_2185-scaled.jpg)

Tyler Bauer [Photo by Lance Ziesch]

Tyler Bauer

For Tyler Bauer, a freshman bull rider from Amaranth, Ontario, Canada, college rodeo has a slightly different slant.

“I’ve been in rodeo for about six years,” Bauer said. “My family has never done anything Western related. My mom did have me learn how to ride horses when I was about 9 or 10 years old. And then when I was 11, I decided that I wanted to get into bull riding. But we’ve never had any rodeo history in my family. We owned a cattle farm. And we always did the work on foot.”

So, although Bauer came from a farm background, he never had the rodeo bug until the day his dad received a call from some guys who were getting ready for a bull riding school.

“My dad was renting a bit of land for extra grazing for the cattle,” he said. “And they ended up calling my dad because their tractor broke down, and they needed to unload some bucking chutes.”

Tagging along with his dad to help unload the chutes, the owner urged him to check out the bull riding school that weekend.

“So we did that Sunday and got talking to a couple of the people who ran it, and he said that I was able to try out next year,” Bauer said. “So I waited a whole year. My mom, said, ‘Oh, just try it once and then never do it again.’ ”

However, that wasn’t to be. Instead of getting it out of his system, that one bull-riding experience hooked him, and he hasn’t looked back.

“The first time I got on, I was fairly nervous,” he said. “I had the butterflies going and everything. But when I left the chute, I mostly just stayed kind of stiff, people would say. But as the years came on, I kind of got more relaxed.”

Although Bauer mainly does bull riding these days, he did try a few other events back in junior high school.

“I did chute dogging and goat tying, but I never had a horse, so I’ve never had the opportunity to do steer wrestling and all of that,” he said.

So, although Bauer doesn’t own a horse, and he doesn’t have the expenses that come with having one—such as buying feed and having a pickup truck, trailer, and tack—he still has out-of-pocket expenses that he needs to cover in order to compete.

“My bull rope definitely cost me over $300,” he said. “I have about a $900 helmet that I have to replace probably soon. I just dropped another over $100 on a new pad and spurs and boot straps.”

In addition, his boots cost $300, his gloves cost between $60 and $70 a pair, his vests cost between $200 and $300 each, and the rosin he needs to coat his bull rope costs about $50 per pound. Rosin, which is a kind of sticky glue, helps riders to grip their ropes more tightly.

All of these costs aside, Bauer said rodeo is definitely still worth it.

“One thing I like about it is the friends you make,” he said. “I didn’t really have too many friends at school, but I did make quite a lot of friends in rodeo. And the only reason why I keep coming back is when a bull bucks me off, it makes me want to ride it more and more.”

![Tyler Bauer rides a bull during rodeo roughstock practice on Sept. 28. [Photo by Lance Ziesch]](https://dc3.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/IMG_2105-scaled.jpg)

Tyler Bauer rides a bull during rodeo roughstock practice on Sept. 28. [Photo by Lance Ziesch]

Because he only competes in bull riding, Bauer only needs to pay one entry fee, which is normally around $70.

“I usually do performance mainly, because there’s not that many bull riders,” he said, referring to the fact that rough-stock events—such as bull riding and bronc riding—don’t typically have slack performances, due to the smaller numbers of contestants.

Thus far in his rodeo career, Bauer’s favorite memory is successfully covering a bounty bull during his rookie year. In rodeo, ‘covering’ refers to a rider staying on the bull the minimum time of 8 seconds. And a bounty bull is a special bull that has a specific payoff attached to it. If the rider, covers the bounty bull, then he gets the extra bounty money.

“I did my first year of open, and they had a bull with a bounty to any rookie rider, if you would cover him,” Bauer said.

So, after getting bucked off of three bulls, Bauer successfully covered the fourth.

“I made it to finals, and then … I ended up covering him, and that put me sixth going into finals,” he said. “With the bounty bull I was like, ‘Oh, I hope I get him at finals, cover him, and I’ll wow everyone.’ So night one, I draw this big Hereford bull. Probably two or three jumps in, I’m off.”

The next night, after drawing the name of a bull that didn’t end up being at the rodeo, Bauer was assigned the first bull that was in the re-ride pen, which happened to be the $500 bounty bull.

“So, it’s night two, I get my rope on, and I’m out of the chute before they even announce my name, because they want to go quick, quick, quick,” he said. “I’m thinking to myself, ‘I’m on. I’m still on. I’m still on.’ And he goes around like three or four spins, and then I’m like, ‘Okay, it has to be long enough because I didn’t hear any buzzer.’ I go to bail… I’m kind of getting excited, and I see people throwing their hats. Next thing I know, I end up covering the bull. I ended up winning the round at finals, and I got the bounty.”

At DC3, Bauer is studying farm and ranch management, and he plans to eventually return to the family farm in Canada after he completes his associate degree. Although, he said he is still considering more rodeo after DC3, such as the International Pro Rodeo Association (IPRA) or International Finals Rodeo (IFR).

“Depends on where I’m going to move to after college,” he said. “[And] whether I’m going to go back home for a few years. I would definitely like to enter a lot of IPRA rodeos, and see if I can make it to the IFR.”

As head coach, Ford definitely knows a thing or two about professional rodeo himself. A two-time Wrangler National Finals Rodeo (NFR) qualifier back in 2005 and 2006, he won the first round of his NFR debut with a 90-point bull ride. And he would go on to finish seventh and 11th in the world standings in 2005 and 2006, respectively.

“I went to school for Rick Smith in Riverton, Wyo.,” he said, referring to his college rodeo coach at Central Wyoming Community College. “I had some ability that he sharpened. He gave me the opportunity to get on and practice and just get my skills fine-tuned. He taught me what it took to be a winner, and I just want to be able to do the same thing for students here.”

For some student-athletes, college rodeo can help set them up for their futures—as it reinforces the concepts of hard work and perseverance—whether it be winning in the realm of professional rodeo or winning in their chosen career paths. It’s also a valuable opportunity for students to get an education while they’re doing what they love, Ford said.

“I’m gonna say 90% of cowboys and cowgirls that rodeo and compete professionally can’t make a living doing it,” he said. “There’s sure enough some cowboys who get the limelight, but what people don’t see is the work they put into it to get to that point. It’s not a sport that many could do.”

However, the sport of rodeo is about far more than winnings, Ford said. It’s “a lifestyle,” and it’s about being a part of the “rodeo family.”

“The rodeo family is like none other, because you’re competing against every one of them,” he said. “But any day you are broke down or you need something, they’ll be right there to help you out.”

This unique relationship is present on the dirt, too, Ford said. It’s a common thing to see contestants helping out in the arena when they are not competing themselves. For instance, during calf roping, one of the other contestants may be pushing the cowboy’s calf out of the chute. And during bull riding, one of the other contestants may be pulling the bull rope before the cowboy’s bull ride.

“You know what I’m saying? Who else is going to do that? Is a cornerback going to be afterwards helping a receiver by telling him, ‘Hey, this is how you can beat me next time?’ They’re not gonna do that,” Ford said. “But cowboys practice together, and they’re there for each other. It’s a close-knit group to be honest with you. That’s one of the best things about it. You make lifelong friends and family through rodeo, which is sometimes more rewarding than the money.”

By Lance Ziesch

DC3 Assistant Director of Marketing and Community Relations